Desert plants are true survivors, thriving in some of the harshest climates on Earth. With limited water, extreme heat, and intense sunlight, these unique plants have developed remarkable adaptations to conserve moisture and endure long droughts. From storing water in swollen stems to shedding leaves in dry spells, each species has its own strategy to make the most of scarce resources. These fascinating desert dwellers offer a glimpse into nature’s ingenuity, using every trick available to withstand their arid environments. Here’s a closer look at some peculiar desert plants and the unusual ways they manage to survive.

Welwitschia (Welwitschia mirabilis)

Native to the Namib Desert, Welwitschia mirabilis is a gymnosperm renowned for its peculiar appearance and longevity, often living for over a thousand years. It produces only two leaves that grow continuously throughout its life, becoming twisted and frayed over time. These leaves have a thick cuticle and sunken stomata, reducing water loss by minimizing transpiration. Its deep taproot system allows it to access underground moisture, while its broad leaves can capture fog, channeling water to the roots. Additionally, it can absorb moisture directly through its leaves, a rare trait among plants. Its ability to survive in one of the driest places on Earth makes it a subject of extensive botanical research. Its resilience and unique adaptations have earned it a place on Namibia’s national coat of arms. Despite its hardy nature, it is vulnerable to climate changes, which threaten its already limited habitat.

Desert Rhubarb (Rheum palaestinum)

Rheum palaestinum, commonly known as desert rhubarb, is indigenous to the Negev Desert. This plant features large, corrugated leaves that form a funnel-like structure, directing rainwater toward its central root system. The leaves’ waxy surface further aids in channeling water efficiently to the roots. This self-irrigating mechanism allows the plant to thrive in arid conditions where other vegetation struggles. Its unique leaf structure ensures it collects water even from sparse rainfall, helping it survive prolonged droughts. Additionally, its deep roots allow it to tap into underground water reserves. Its highly efficient water management makes it an exceptional model of desert adaptation.

Saguaro Cactus (Carnegiea gigantea)

The towering saguaro cactus, Carnegiea gigantea, is an iconic symbol of the Sonoran Desert. This cactus has developed accordion-like pleats that expand and contract, allowing it to store vast amounts of water after a rainfall. The thick, waxy skin reduces water loss by limiting transpiration and reflects sunlight to keep the plant cool. Its roots spread wide and near the surface to quickly absorb moisture from light rains, while deep taproots anchor the plant and provide access to groundwater. The saguaro’s ribs act as water storage chambers, enabling it to store enough water to survive for months without rain. During prolonged droughts, it can rely on these reserves to stay hydrated. It also uses its height to capture rain more effectively, funneling it down to its base.

Lithops (Lithops spp.)

Lithops, also known as “living stones,” are small, stone-like succulents native to southern Africa. Their unique camouflage, mimicking the surrounding pebbles, reduces the likelihood of water loss by shielding them from sun exposure. They have only two leaves that form a window-like top, allowing light in while reducing surface area to minimize evaporation. The thick, fleshy leaves store water, which sustains the plant through the dry season. They remain dormant during the hottest months, conserving energy and water until cooler conditions return. This adaptation helps them survive in environments where rainfall is infrequent and unpredictable. They also absorb moisture from morning dew, supplementing their minimal water intake. Their remarkable mimicry and minimal water needs make them masters of desert survival.

Ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens)

The ocotillo, Fouquieria splendens, is a spiny, drought-tolerant plant native to the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. Unlike most plants, it sheds its leaves during dry periods to conserve water, leaving only thorny stems. When it rains, the plant quickly sprouts new leaves to take advantage of the moisture and engage in photosynthesis. This cycle of shedding and regrowing leaves can happen multiple times a year, allowing the ocotillo to maximize water use efficiency. Its deep roots reach underground water, ensuring survival during prolonged droughts. Additionally, its waxy stem coating prevents water loss by limiting transpiration. This adaptive cycle of leaf growth and shedding is critical for its survival in arid landscapes.

Baobab Tree (Adansonia spp.)

The baobab tree, Adansonia, is known as the “tree of life” due to its ability to store massive amounts of water in its thick, trunk-like stem. Found in arid regions of Africa and Australia, it can store thousands of liters of water during the rainy season. Its bark is smooth and spongy, allowing it to absorb water and retain it for extended periods. Its leaves are shed during dry periods to reduce water loss, and its branches resemble roots, earning it the nickname “upside-down tree.” They rely on stored water during droughts, which helps sustain local wildlife. The water-storing ability also aids in its survival against wildfires, a frequent occurrence in its native habitats. This remarkable water reserve supports the tree’s longevity, with some living for over a thousand years.

Barrel Cactus (Ferocactus spp.)

Barrel cacti, belonging to the genus Ferocactus, are known for their ribbed, cylindrical shape, which helps them conserve water. Native to the American Southwest, they have deep, fleshy tissues that store water, keeping the plant hydrated during extended droughts. Their ribs allow the plant to expand when water is available and contract when resources are scarce. They often lean toward the south to reduce direct sun exposure, minimizing water loss through evaporation. Its thick skin and spines provide additional protection against the sun and animals that may seek its stored water. They have shallow root systems that spread wide to capture rain quickly before it evaporates. This efficient water conservation strategy makes them resilient desert survivors.

Rose of Jericho (Selaginella lepidophylla)

Commonly known as the “resurrection plant,” Selaginella lepidophylla can survive extreme dehydration in the deserts of Mexico and the southwestern United States. It curls up into a tight ball during dry conditions, reducing its surface area to minimize water loss. When exposed to moisture, it unfurls and resumes photosynthesis within hours, a process it can repeat multiple times. Its cells contain high concentrations of protective sugars, preventing cell damage during dehydration. These sugars act as a buffer, allowing the plant to survive without water for years. This remarkable ability to “resurrect” itself has made it a symbol of resilience and renewal. Its unique adaptations are a testament to its survival in harsh desert climates.

Sand Verbena (Abronia villosa)

The sand verbena, Abronia villosa, is a flowering plant native to the deserts of the southwestern United States. It has evolved to take advantage of the desert’s brief rainy season, growing quickly and blooming when water is available. It produces hairy leaves that reduce water loss by trapping a layer of moist air near the leaf surface. Its deep taproot allows it to access underground water, helping it survive even in drought. Its seeds are also adapted to withstand prolonged dry spells, remaining dormant until conditions are favorable. This strategy allows sand verbena to reemerge when moisture returns, ensuring survival in its arid habitat. Its vibrant flowers attract pollinators, essential for its reproduction in harsh environments.

Creosote Bush (Larrea tridentata)

The creosote bush, Larrea tridentata, is one of the most resilient desert plants, thriving in the American Southwest and Mexican deserts. It has adapted by developing waxy leaves that reduce water loss through evaporation. It also produces a resin that creates a protective coating, shielding it from intense sunlight. It has a unique root system that spreads widely and deeply to absorb any available moisture. During extreme drought, it can shed leaves to further conserve water. Its seeds are coated with chemicals that inhibit germination until conditions improve, ensuring that new growth occurs during favorable times. Its longevity and drought tolerance make it one of the longest-living plants in desert ecosystems.

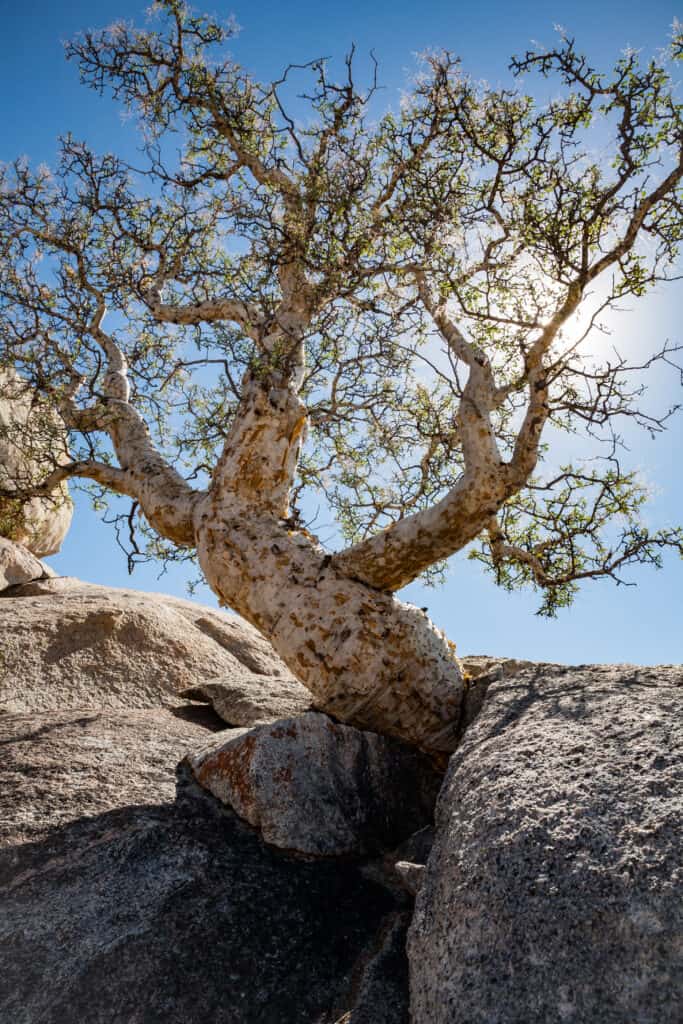

Elephant Tree (Bursera microphylla)

Native to the Sonoran Desert, the elephant tree, Bursera microphylla, stores water in its thick, swollen trunk. This storage capability allows it to endure long periods without rain. Its small, waxy leaves minimize water loss by reducing surface area, and the tree sheds them during dry spells to further conserve moisture. It has shallow roots that spread widely to capture water from infrequent rains. Additionally, it excretes aromatic resins that deter herbivores, preserving its water resources. Its unique appearance and water-storing capacity have made it a fascinating species among desert flora. These adaptations make it highly resilient to the desert’s extreme climate conditions.

This article originally appeared on Rarest.org.

More from Rarest.org

21 Forest Plants That Thrive in Low-Light Conditions

Forest floors are often shaded, but that doesn’t mean they’re barren. Many plants thrive in low-light conditions, adding greenery and life to the darkest corners of the woods. Read More.

15 Rare and Exotic Amphibians Thriving in Remote Jungles

Deep within the world’s most remote jungles, a diverse range of rare and exotic amphibians thrive, often hidden from human view. These remarkable creatures have evolved unique traits to survive in their specific environments, from vibrant colors that ward off predators to extraordinary abilities like gliding or regenerating limbs. Read More.

16 Unique Flora and Fauna Found Only in Isolated Ecosystems

Isolated ecosystems have given rise to some of the most unique plants and animals on Earth. These regions, often cut off from other landmasses for millions of years, allow species to evolve in ways that are found nowhere else. Read More.