Art has always been a way for artists to express their creativity, challenge societal norms, and push the boundaries of what’s considered conventional. Over the years, there have been numerous art movements that not only defied traditional styles but also redefined the very nature of art itself. From chaotic assemblages to thought-provoking performances, these bizarre movements questioned everything from the purpose of art to its place in society. In this article, we’ll explore 16 of the most unusual and groundbreaking art movements that challenged conventional wisdom and reshaped the art world in unexpected ways.

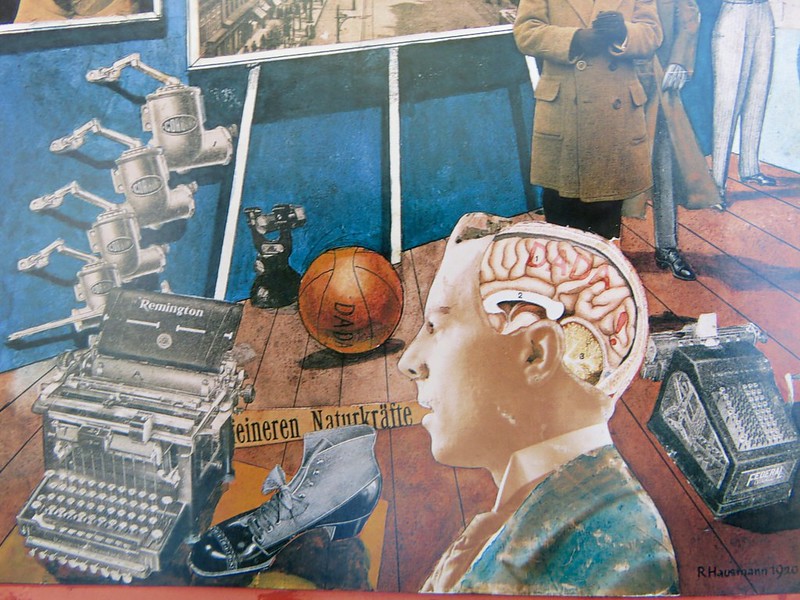

Dadaism

Emerging in the early 20th century, Dadaism was a radical response to the horrors of World War I. Rejecting the rationality and logic that had led to the war, Dada artists embraced absurdity and chaos. They produced works that often involved random elements, such as collage, photomontage, and nonsensical poetry. Dadaism was a direct challenge to the established norms of art and culture, and it sought to destroy the notion of art as something sacred. The movement was international, with key centers in Zurich, Berlin, and New York. Notable figures like Marcel Duchamp and Hannah Höch became synonymous with Dada’s rebellious spirit. Dada was not merely an artistic movement; it was a statement against societal norms, political systems, and the very concept of art itself.

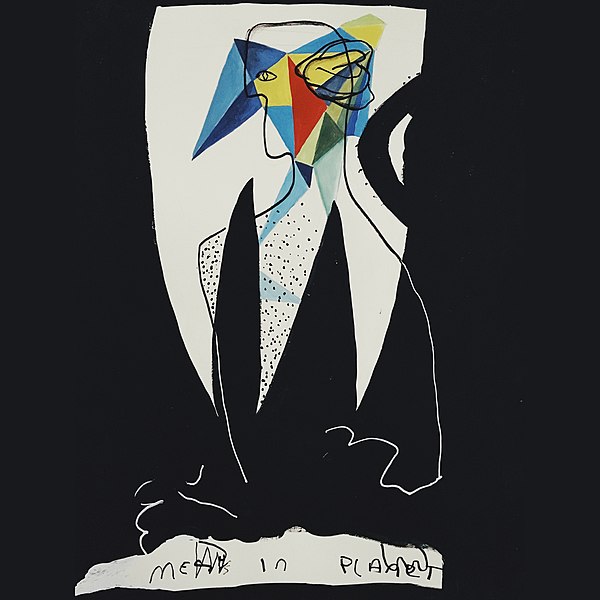

Surrealism

Surrealism began in the 1920s as a movement dedicated to exploring the unconscious mind. Influenced by Freudian psychology, surrealists sought to depict dream-like states and irrational, fantastical imagery. Artists like Salvador Dalí and René Magritte created vivid, distorted scenes that challenged the viewer’s understanding of reality. They often incorporated juxtapositions and absurd combinations of everyday objects. Surrealism’s goal was to liberate the mind from the constraints of logical thought and to tap into the deeper layers of human experience. It grew into a broad cultural phenomenon, affecting literature, film, and theatre. Despite its complex theoretical underpinnings, Surrealism’s impact on visual art was undeniable, leaving an indelible mark on 20th-century culture.

Futurism

Futurism emerged in Italy in the early 20th century, with an emphasis on speed, technology, and modernity. Its founders, such as Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, rejected the past and embraced a dynamic vision of the future. Futurist artworks often depicted motion, energy, and the rapid pace of industrialization, using fragmented shapes and bold colors. The movement was strongly influenced by advances in technology, particularly the rise of the automobile and the airplane. However, Futurism also had a darker side, as its proponents sometimes allied with Fascist ideology. Despite its controversial political leanings, Futurism had a profound influence on later art movements like Cubism and Abstract Expressionism. It marked a significant departure from traditional representation in art, focusing instead on capturing the essence of the modern, fast-paced world.

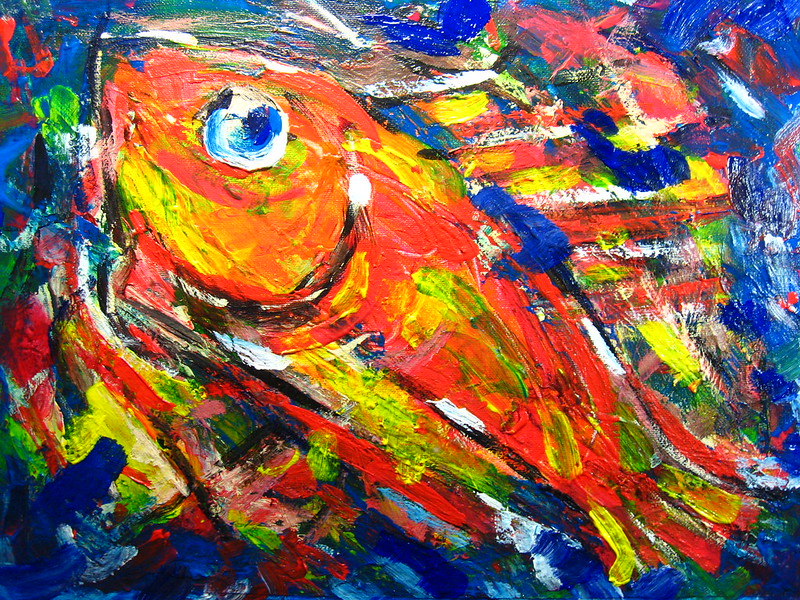

Abstract Expressionism

Developing in the United States in the 1940s and 1950s, Abstract Expressionism was a revolutionary movement that emphasized spontaneous, emotional expression over representational accuracy. Artists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning rejected traditional artistic techniques in favor of gestural brushstrokes, vibrant colors, and raw emotional content. The movement’s focus was on the process of painting itself, rather than the finished product. Abstract Expressionists believed that their work should convey the artist’s inner emotions and unconscious thoughts. They often created large-scale works, allowing their physical engagement with the canvas to become a key part of the art itself. This movement also laid the foundation for later developments in contemporary art, influencing Minimalism and Conceptual Art. Though initially criticized for being chaotic and non-representational, Abstract Expressionism eventually became a cornerstone of modern art.

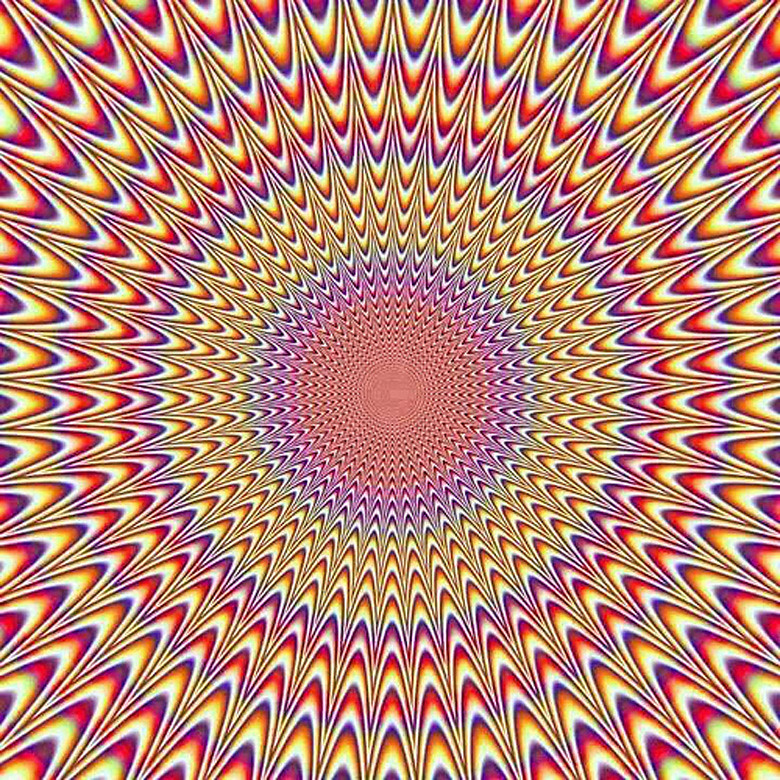

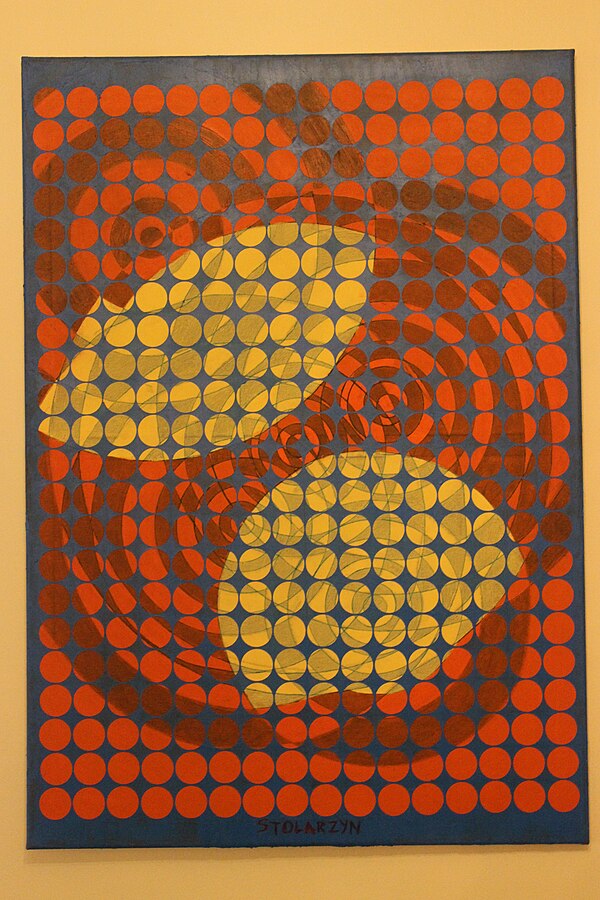

Op Art

Op Art, short for “Optical Art,” emerged in the 1960s as an exploration of visual perception. It is defined by the use of geometric patterns and color contrasts that create optical illusions of movement or depth. Artists like Bridget Riley and Victor Vasarely utilized precise lines, shapes, and color contrasts to trick the eye into seeing dynamic motion or vibrating surfaces. Op Art’s focus on perceptual experience challenged traditional notions of form and representation in art. Unlike Abstract Expressionism, which emphasized emotional content, Op Art was primarily concerned with visual perception and its effects on the viewer. This movement, while rooted in abstraction, often had a scientific or mathematical approach to composition. Op Art quickly gained popularity, especially in commercial design and advertising, due to its visual appeal and psychological impact.

Minimalism

Minimalism, which emerged in the 1960s, rejected the emotional and gestural approach of Abstract Expressionism in favor of simplicity and objectivity. Artists like Donald Judd and Frank Stella created artworks using clean lines, basic shapes, and industrial materials. The movement sought to remove any extraneous elements, focusing solely on the essence of form and color. Minimalist art often utilized repetition and geometric precision to explore the relationship between space, viewer, and object. Unlike previous movements, which were heavily imbued with personal expression, Minimalism emphasized the artwork as an autonomous entity. This departure from traditional artistic values made Minimalism a revolutionary approach in the art world. Over time, it influenced design, architecture, and even music, making a lasting impact on contemporary aesthetics.

Fluxus

Fluxus was an avant-garde movement that originated in the early 1960s, emphasizing experimentation and cross-disciplinary collaborations. Artists in the Fluxus collective, including George Maciunas and Yoko Ono, sought to break down the barriers between art and life. Fluxus works often involved performance, everyday objects, and unconventional materials. They favored spontaneous, playful gestures over traditional artistic processes and were highly influenced by the Dada movement’s anti-art sentiments. Fluxus performances could range from simple instructions to absurd actions, challenging the notion of the artist as a solitary genius. The movement’s emphasis on participatory art also blurred the lines between artist and audience. Fluxus’ radical approach to art-making remains an important part of the legacy of conceptual art.

Psychedelic Art

Psychedelic Art emerged in the 1960s, heavily influenced by the counterculture movement and the use of hallucinogenic substances. It is characterized by vibrant colors, surreal imagery, and intricate, flowing patterns designed to evoke altered states of consciousness. The style was frequently used in posters, album covers, and other media associated with the music scene of the time, particularly in the psychedelic rock genre. Artists like Wes Wilson and Rick Griffin created works that mimicked the sensory overload of a psychedelic experience. The movement incorporated elements of Art Nouveau and Surrealism but with a distinctly mind-bending twist. Psychedelic Art pushed the boundaries of visual representation, often merging reality with hallucination. Its influence can still be seen today in various forms of pop culture, from fashion to digital design.

Gothic Revival

The Gothic Revival movement, which began in the mid-19th century, was a return to medieval aesthetics, but with a highly stylized, often exaggerated twist. The movement sought to resurrect the grandeur and drama of Gothic architecture and design, while infusing it with Victorian-era sensibilities. Artists and architects, including Augustus Pugin and Charles Barry, embraced pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and stained glass, but often used these elements in unusual, exaggerated forms. The Gothic Revival was both a nostalgic look back at the past and a rejection of the industrialization of society. It influenced everything from literature to interior design, with a focus on the mystical and the macabre. While it was initially a reactionary movement, Gothic Revivalism laid the groundwork for later aesthetic experiments in art and architecture. It also contributed to the Romanticism movement’s emphasis on the mysterious and the sublime.

Art Brut

Art Brut, or “raw art,” was coined by French artist Jean Dubuffet to describe art created outside the boundaries of official culture and the academic tradition. This movement celebrated the creativity of self-taught artists, including those in mental hospitals, prisons, and other marginal environments. Dubuffet’s own works, often characterized by crude, aggressive lines and non-traditional materials, became synonymous with Art Brut’s ideals. Rejecting conventional aesthetics, the movement valued spontaneous, unpolished expression over refined technique or formal training. Art Brut had a profound influence on the development of outsider art, which sought to give voice to those outside the mainstream art world. Dubuffet’s approach challenged the elitist gatekeeping of the art establishment. It highlighted the universal nature of creativity, regardless of social or educational background.

Performance Art

Performance Art emerged as an experimental form of art in the 1960s, blurring the lines between art and life. Artists like Marina Abramović and Allan Kaprow used their bodies as a medium, often incorporating audience participation or durational aspects. Unlike traditional theater, Performance Art is usually unscripted and can take place in various public or private spaces. The focus is not on creating a finished artwork but on the experience and interaction between artist and viewer. Performance Art challenges the notion of the artist as an isolated creator, instead exploring collective, temporal, and social aspects of art. It has also been used to comment on political, social, and cultural issues. Its ephemeral nature makes it difficult to categorize, challenging traditional ideas of permanence in art.

Situationism

Originating in the 1950s, the Situationist International aimed to critique the commercialization of culture and art. It emphasized the importance of creating situations that disrupted the monotony of daily life. Situationist artists, led by figures like Guy Debord, advocated for ‘dérive’ or the drifting through urban spaces in a way that encouraged spontaneous, uninhibited experiences. The movement sought to use art as a tool for social and political change, challenging the consumer-driven culture of the time. They believed that art should not be an object but an experience that alters the viewer’s perception of the world. By reclaiming public spaces and creating art in the form of disruptions, they reshaped the boundaries of what could be considered ‘art.’ Their influence on modern protest culture and guerrilla art is still felt today.

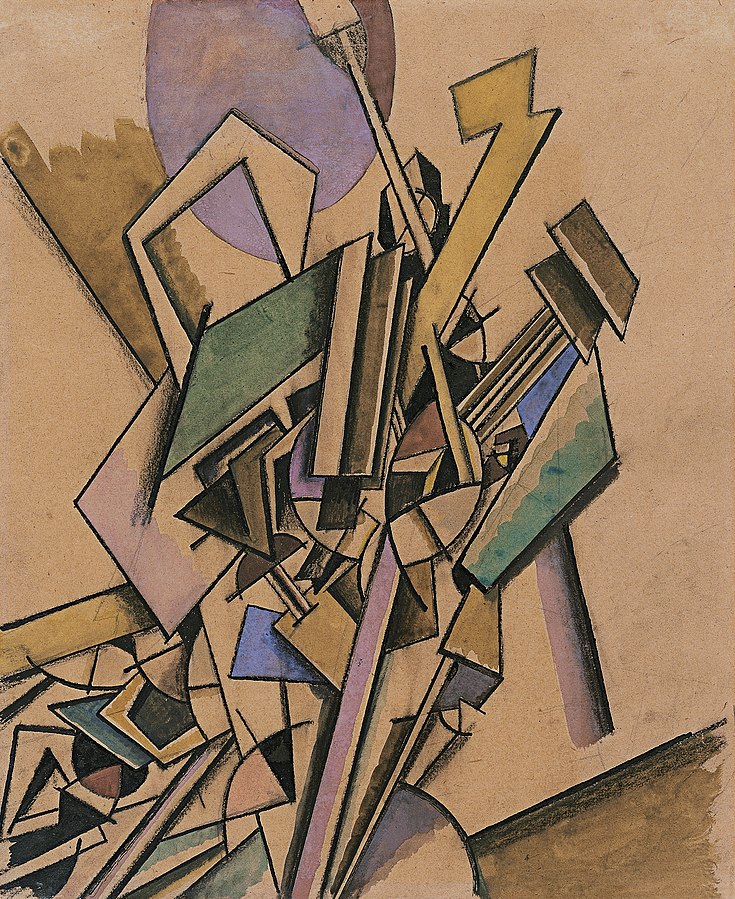

Vorticism

Vorticism was a short-lived but intense movement in early 20th-century Britain that aimed to combine the dynamism of Futurism with the abstract angularity of Cubism. Led by artist Wyndham Lewis, Vorticism sought to capture the energy and rhythm of modern life, particularly in industrialized urban environments. It embraced bold, jagged lines, geometric shapes, and vibrant colors, rejecting traditional depictions of nature and the human form. The movement also incorporated elements of machinery and technology, reflecting the technological advancements of the time. Vorticism, although overshadowed by other modernist movements, provided a distinctive voice in the avant-garde scene. The movement’s name, derived from the word “vortex,” symbolized the energy and power that artists wished to convey through their work. Vorticism questioned the role of art in the modern world, challenging both its form and content.

Kinetic Art

Kinetic Art, which gained popularity in the mid-20th century, revolved around the idea of motion and the relationship between the viewer and the work. Artists like Alexander Calder and Jean Tinguely created sculptures that could move, either through mechanical or natural forces. Kinetic Art shattered the static, static nature of traditional visual art by introducing motion as a central component. These works often required the active participation of the viewer, who could influence the movement or arrangement of the piece. Kinetic artists sought to incorporate modern scientific and technological advancements, blurring the line between art, engineering, and physics. This type of art reflected the changing pace of the modern world and offered a dynamic viewing experience. The movement’s embrace of motion reshaped how people interacted with art, making it an ongoing, ever-changing process rather than a static object.

Bauhaus

Although not often considered bizarre in its historical context, the Bauhaus school of design (1919-1933) defied traditional norms by merging art, crafts, and industrial design in a revolutionary way. Founded by Walter Gropius in Germany, the school advocated for functionality and simplicity, eschewing ornamental design in favor of clean lines and utilitarian forms. Bauhaus artists and architects believed that art should be accessible to all, integrating design into everyday life and mass production. The movement’s influence extended far beyond architecture, impacting furniture design, typography, and even textiles. Bauhaus emphasized the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration, bringing together artists, architects, and engineers to solve problems. Its minimalist, geometric approach to design challenged the ornamental, historical styles that dominated the art world at the time. Despite its relatively short existence, Bauhaus left a profound legacy on modern art, design, and architecture.

Neo-Expressionism

Neo-Expressionism, which emerged in the late 1970s and 1980s, was a reaction against the conceptual and minimalist art movements that had dominated the previous decades. Artists like Julian Schnabel and Anselm Kiefer revived the emotional intensity and bold, figurative forms of earlier Expressionism, but with a modern, often chaotic twist. Their works were characterized by aggressive brushstrokes, vivid color palettes, and distorted forms that conveyed deep emotional or psychological states. Neo-Expressionism rejected the cold intellectualism of Minimalism and instead embraced the raw, visceral energy of the human experience. The movement also featured a return to narrative and symbolism, often exploring themes of identity, trauma, and history. Critics initially rejected Neo-Expressionism for its perceived return to tradition, but its confrontational energy resonated with a new generation of viewers. As a result, Neo-Expressionism became a defining movement of 1980s art, marking a shift toward more emotionally charged and subjective expressions of reality.

This article originally appeared on Rarest.org.

More From Rarest.Org

Japan has a rich and storied brewing history, with beer production dating back over a century. The country’s oldest breweries have shaped the beer landscape both domestically and internationally, blending traditional brewing methods with modern innovations. Read more.

Bicycles have played a crucial role in shaping transportation throughout history, offering a practical, affordable, and environmentally friendly way to get around. From early designs that barely resembled the bikes we know today, to the more sophisticated models that revolutionized travel, each advancement brought us closer to the bicycles we rely on now. Read more.

The music industry is powered by a few major record labels that dominate global markets, helping artists reach audiences around the world. They generate billions in revenue by managing diverse rosters of artists, from rising stars to global icons, while adapting to digital trends and streaming platforms. Read more.