Throughout history, many animal species that were once abundant have vanished from the Earth, often due to human activity. These extinctions are a reminder of the delicate balance of ecosystems and how quickly a species can disappear when its environment is disrupted. From birds to mammals, each of these played an important role in their habitats before they were lost forever. In this article, we explore these species, providing a glimpse into their former abundance and the reasons behind their extinction.

Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius)

The passenger pigeon, once considered the most numerous bird species in North America, saw its population in the hundreds of millions before its tragic decline. Flocks of these birds were so vast that they could darken the sky for hours. Found primarily in eastern North America, they migrated in large, coordinated groups, nesting in dense colonies. However, by the late 19th century, habitat destruction, overhunting, and the commercial demand for pigeon meat caused their rapid decline. The last known passenger pigeon, named Martha, died in captivity in 1914 at the Cincinnati Zoo. Despite their once-massive numbers, their inability to adapt to human-induced changes contributed to their extinction. Their loss is a poignant reminder of how quickly nature can be disrupted when human demands outpace ecological balance. Their extinction was largely driven by unsustainable hunting practices, with millions killed each year for meat. Efforts to protect them came too late as their populations had already dwindled too far to recover.

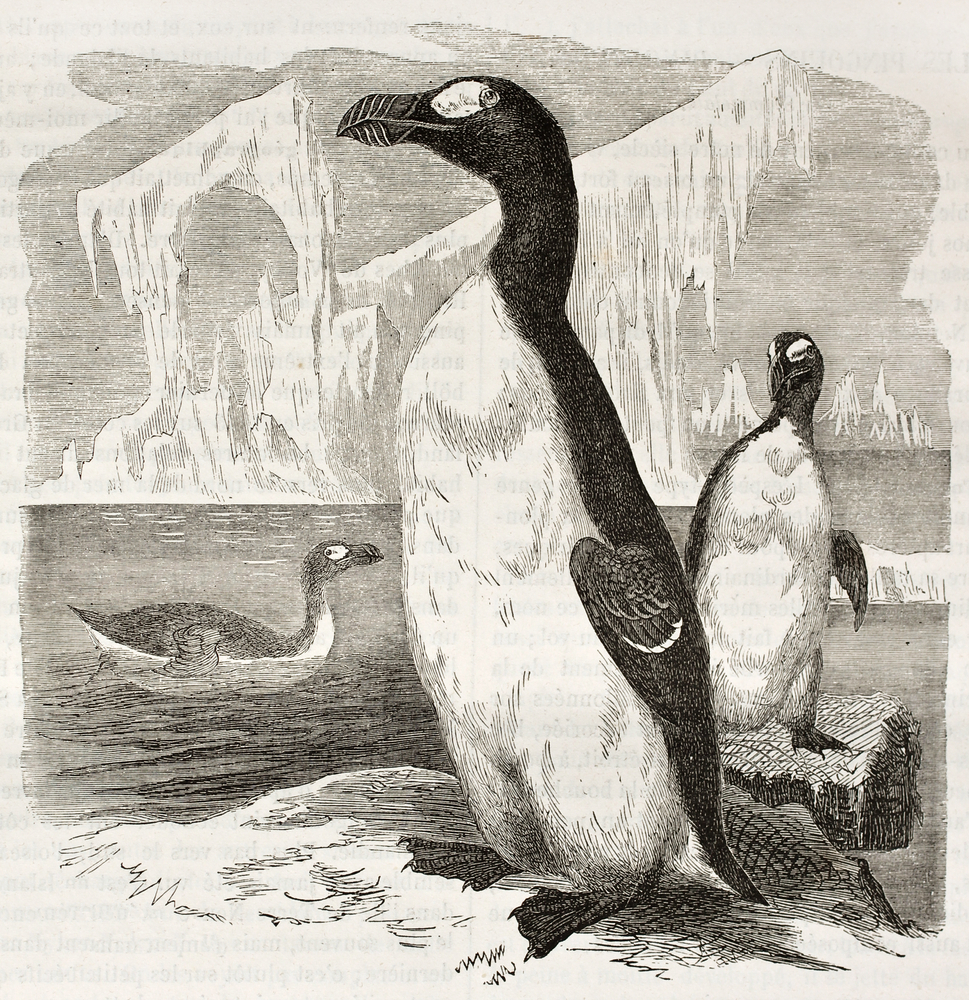

Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis)

The great auk was a large, flightless bird that once thrived along the coasts of the North Atlantic, from Canada to northern Europe. Standing about 30 inches tall, with a striking black-and-white plumage, it was a skilled swimmer and diver. These birds lived in large colonies on rocky islands, where they laid eggs in the summer months. By the 16th century, they were heavily hunted for their meat, eggs, and feathers. The introduction of human predators, combined with environmental changes, led to their rapid decline. By 1844, the last known great auk was killed on an island off the coast of Iceland. Today, they are remembered as one of the most prominent examples of human-induced extinction. Notably, their disappearance marked a devastating loss in marine ecosystems, as they were integral to the regulation of local fish populations. Its extinction has inspired numerous conservation efforts focused on protecting vulnerable seabird species.

Woolly Mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius)

The woolly mammoth, a massive herbivorous mammal closely related to today’s elephants, once roamed much of the northern parts of North America, Europe, and Asia. With its long, curved tusks and thick fur, it was well adapted to cold, Ice Age climates. These animals formed large herds and played an essential role in their ecosystem by shaping vegetation and providing food for predators. However, overhunting by early humans, combined with climate change that led to the loss of their preferred habitat, caused their decline. By around 4,000 years ago, the last population of woolly mammoths disappeared from Wrangel Island, in the Arctic Ocean. Although their extinction was gradual, it was hastened by the changing environment and human hunting practices. Today, they remain one of the most iconic symbols of the Pleistocene epoch. Some scientists are exploring the possibility of “resurrecting” woolly mammoths through genetic engineering, using the DNA of preserved mammoths and modern-day elephants. The prospect of this raises intriguing questions about biodiversity and climate change solutions.

Spix’s Macaw (Cyanopsitta spixii)

Spix’s macaw, also known as the Little Blue Macaw, is native to Brazil, where it once thrived along the Rio São Francisco. With its vibrant blue feathers and distinctive calls, it was a striking bird, prized in aviculture for its beauty and intelligence. Unfortunately, habitat destruction, combined with poaching and the illegal pet trade, decimated its population by the 1980s. In the wild, it was declared extinct by the early 2000s, with the last confirmed sighting occurring in 2000. However, a small number of birds still exist in captivity, primarily in breeding programs aimed at reintroducing them to the wild. Conservation efforts have been ongoing, and in 2018, a group of Spix’s macaws was released into the Brazilian wild. Though challenges remain, these efforts have renewed hope for the species’ survival. Recent developments in captive breeding and rewilding efforts have led to small successes, though its long-term future remains uncertain. The reintroduction project highlights the importance of preserving the species’ natural habitat for a sustainable comeback.

Dodo (Raphus cucullatus)

The dodo is perhaps the most famous example of human-induced extinction, a flightless bird that once lived on the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. These birds had no natural predators on their island, allowing their population to grow without the need to fear. Measuring about 3 feet tall, they were a gentle, herbivorous species that fed on fruits and seeds. However, with the arrival of European explorers in the 16th century came rats, pigs, and monkeys that preyed on dodo eggs. Human hunters also sought the birds for food, and by the late 1600s, it was gone. The exact date of their extinction is debated, but it is believed to have been around 1681. Today, it is an emblem of the fragility of island ecosystems. Despite their extinction, its legacy continues to shape conservation discussions, particularly regarding the introduction of invasive species to isolated ecosystems. Its extinction also catalyzed early ecological studies regarding the impact of human activities on species survival.

Caribbean Monk Seal (Neomonachus tropicalis)

The Caribbean monk seal was a species of seal that lived in the warm waters of the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Bahamas. They were known for their rounded bodies and distinctively sleek fur, thriving in tropical and subtropical waters. They were once abundant in these regions but were hunted for their pelts, oil, and meat from the 18th century onwards. Overfishing in the Caribbean further depleted their food sources, and by the mid-20th century, the species had all but vanished. In 1952, the last confirmed sighting of a Caribbean monk seal occurred, leading to its official extinction by the 1960s. Although conservationists made efforts to protect the seals, it was too late to halt their decline. It is now considered a cautionary tale of the impact of overexploitation. Despite their extinction, efforts to restore marine ecosystems in the Caribbean continue, focusing on the preservation of remaining seal populations. Conservationists are also working to prevent the same fate from befalling other marine mammals.

Pinta Island Tortoise (Chelonoidis Abingdon)

Pinta Island tortoises once inhabited Pinta Island in the Galápagos Archipelago. These massive reptiles, which could weigh up to 550 pounds, were slow-moving, herbivorous creatures that lived for over 100 years. The introduction of invasive species, such as rats and pigs, along with habitat destruction, significantly reduced their numbers. The last known Pinta Island tortoise, a male named Lonesome George, died in 2012, marking the official extinction of the species. Though efforts were made to preserve them, including breeding programs for other species in the Galápagos, it could not be saved. Lonesome George was the last representative of his species, and his death symbolized the loss of a unique evolutionary branch. Today, the extinction of this animal highlights the delicate nature of island biodiversity. Conservationists have shifted their focus to restoring the populations of other endemic tortoises in the Galápagos, hoping to prevent further extinctions. The lessons learned from its demise continue to influence conservation strategies worldwide.

Tasmanian Tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus)

The thylacine, also known as the Tasmanian tiger, was a carnivorous marsupial native to Tasmania, Australia, and New Guinea. It was the largest carnivorous marsupial of modern times, resembling a dog with a kangaroo-like tail and distinctive tiger-like stripes on its back. It was once abundant across its range, but hunting, habitat destruction, and competition with introduced species such as dogs and foxes led to its decline. By the early 20th century, the population was largely confined to Tasmania, where it became the target of organized eradication campaigns. The last known thylacine died in captivity in 1936 at the Hobart Zoo, marking the official extinction of the species. Despite occasional unconfirmed sightings, there has been no evidence of the thylacine surviving in the wild. Its extinction highlights the vulnerability of species that are already under stress from human activities and invasive species. Recent scientific advances have sparked discussions around the possibility of “de-extincting” the thylacine through cloning or genetic engineering, though it remains controversial.

Pyrenean Ibex (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica)

The Pyrenean ibex, a subspecies of the Spanish ibex, once inhabited the mountainous regions of the Pyrenees, straddling the border between France and Spain. With its impressive curved horns and sturdy build, it was well-adapted to life in steep, rocky terrain. It was a resilient species, able to thrive in harsh environments with little competition from other large herbivores. However, due to hunting pressure and the destruction of its alpine habitat, its population began to dwindle in the 19th century. By the early 20th century, the species had become extinct in the wild, with the last confirmed sighting in 2000. Despite attempts to conserve the species through habitat protection, it could not be saved. In 2003, a single individual was cloned from preserved tissue, but the clone lived only a few minutes, highlighting the complexity of bringing back extinct species. While some conservationists have proposed using cloning technology to potentially revive it, the ethical and ecological challenges are significant.

Javan Tiger (Panthera tigris sondaica)

The Javan tiger, a subspecies of tiger once found on the Indonesian island of Java, was a formidable apex predator and a vital part of the island’s ecosystem. They were known for their smaller size compared to other tiger subspecies, but their agility and strength made them expert hunters. The island of Java, with its dense forests and rugged terrain, provided a perfect environment for them to thrive. However, as human populations expanded and deforestation began to take hold in the 19th and 20th centuries, its natural habitat was increasingly fragmented. The rapid destruction of their habitat, combined with poaching and the depletion of their prey species, led to a sharp decline in their numbers. By the 1970s, the last confirmed sighting of this tiger was recorded, and it is believed to have been extinct by the early 1980s. Conservationists have often pointed to its extinction as an example of how the combination of habitat loss and human encroachment can rapidly drive a species to extinction. There are ongoing debates about whether it could ever be reintroduced to Java, with some advocating for the restoration of its native environment as a possible solution.

This article originally appeared on Rarest.org.

More from Rarest.org

20 Keystone Species That Play a Crucial Role in Their Habitats

Keystone species are essential to maintaining the balance of their ecosystems. Without them, the structure of the habitat could change dramatically. These species often influence many other organisms in their environment, helping to regulate populations and maintain biodiversity. Read More.

21 Strange Geological Formations Found in Uninhabited Lands

The Earth hides some of its most extraordinary formations in uninhabited regions. These remote landscapes are home to geological wonders that seem almost otherworldly. Read More.

18 Rare and Exotic Fruits You Can Grow at Home

Growing your own exotic fruits at home is an exciting way to add rare flavors to your garden. Many of these fruits offer unique tastes that are hard to find in stores. Read More.