Many indigenous tribes around the world have practiced rich and meaningful traditions for centuries, each deeply connected to their culture, environment, and spiritual beliefs. However, as modernization and outside influences have spread, many of these customs have faded into obscurity. From spiritual rituals to unique survival techniques, these forgotten traditions once played a central role in the daily lives of their communities. Exploring these practices helps us better understand the deep cultural roots and wisdom that shaped these societies. While some are being revived, many remain forgotten, offering a glimpse into the worldviews of indigenous peoples.

Dream Weaving – Ojibwe Tribe (North America)

Dream weaving was a significant part of Ojibwe spirituality. The creation of intricate dreamcatchers was believed to filter out bad dreams, letting only good ones pass through. Elders taught younger generations how to delicately weave the strands, each one representing a part of life’s journey. Though these were once made by hand, modern versions are mass-produced, losing their spiritual essence. In Ojibwe culture, the practice connected deeply to the spirit world and provided protection for children. As the tribe modernized, the depth of this tradition has gradually faded.

Fire Walking – Māori (New Zealand)

Fire walking is an ancient Māori rite of passage symbolizing courage and resilience. Warriors would walk barefoot over burning embers, proving their bravery to their community. This practice was deeply connected to tribal identity, reinforcing strength and mental toughness. Over time, with the influence of colonialism and modernity, fire walking was largely forgotten. Although there are occasional revivals of the tradition in cultural celebrations, its deep spiritual meaning has been diminished. The original ritual connected participants to their ancestors and the forces of nature, a vital part of Māori life that is rarely seen today.

Potlatch Ceremonies – Tlingit (Pacific Northwest)

The Potlatch was an elaborate gifting ceremony among the Tlingit people, representing wealth, power, and community bonds. Chiefs would host these events to redistribute wealth, share stories, and assert their leadership. In many ways, the Potlatch was the backbone of social order and tribal identity. However, colonial governments banned it in the late 19th century, viewing it as a threat to capitalist values. While it has been reintroduced in certain areas, its original grandeur and widespread practice have significantly declined. Potlatch ceremonies today tend to be symbolic rather than the vast, multi-day gatherings they once were.

Initiation Dance – Himba (Namibia)

For the Himba, the initiation dance marked the transition from childhood to adulthood. Young girls would perform this dance adorned with intricate jewelry, beads, and ochre covering their skin, representing beauty and fertility. The dance was both a celebration and a spiritual rite, connecting the individual to ancestors. Over the years, many Himba traditions have been diluted due to the pressures of modernization and tourism. Fewer Himba women now undergo this rite, and when it does occur, it is often for the benefit of outsiders. The deeper meanings behind the dance, which once carried a heavy cultural significance, have largely been forgotten.

Body Scarification – Dinka (South Sudan)

Among the Dinka, body scarification was a deeply spiritual practice symbolizing maturity, bravery, and status within the tribe. Young men, in particular, would receive elaborate facial scars during ceremonies, marking their transition into adulthood. These scars represented their ability to endure pain and hardship, critical traits for warriors. Due to modernization and outside influences, this practice has faded significantly. Today, many younger Dinka reject scarification, associating it with outdated customs rather than pride in their heritage. As such, a tradition once central to identity is now seen only rarely.

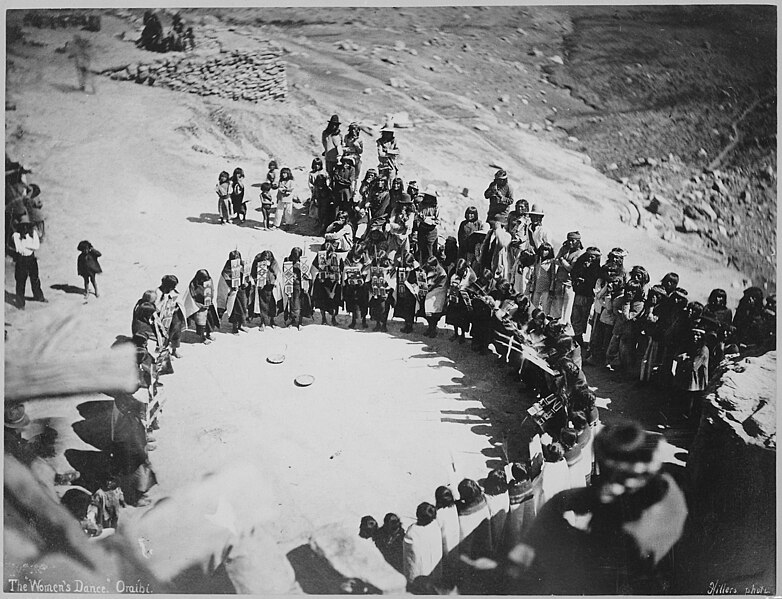

Rain Dance – Hopi Tribe (Southwest USA)

The Hopi people performed rain dances to call upon the spirits to bring water to their arid lands. These complex dances involved intricate movements and costumes, designed to please the gods and ensure a bountiful harvest. The entire community took part, from elders to children, making it a deeply unifying event. However, as modern irrigation methods became available, the necessity for the rain dance diminished. Though some Hopi still perform it during cultural festivals, it has largely lost its original urgency. The sacred connection between the Hopi and the natural world that the dance represented is now a fading memory.

Eagle Hunting – Kazakh Nomads (Mongolia)

Eagle hunting was a revered tradition among Kazakh nomads, requiring both skill and a deep connection with nature. Hunters would train golden eagles from a young age, using them to capture prey in the harsh Mongolian landscape. This ancient practice was passed down from father to son, ensuring that each generation maintained a bond with their surroundings. As modernization spread, fewer young men took up eagle hunting, opting instead for more contemporary professions. Today, eagle hunting exists primarily as a cultural spectacle rather than a necessity for survival. While some Kazakhs keep the tradition alive, its original purpose and prestige are slowly disappearing.

Shamanic Drumming – Sámi (Northern Europe)

Shamanic drumming was a critical part of Sámi spiritual practice, used to communicate with the spirit world and heal the sick. The repetitive beat was said to put both the shaman and the participants in a trance, connecting them to their ancestors and nature. As Christianity spread through Northern Europe, shamanic practices, including drumming, were banned. Over time, the tradition nearly disappeared, practiced only in secret or by a select few. Today, the tradition is being slowly revived in cultural contexts, but its original spiritual purpose is largely lost. Once an essential part of Sámi life, the drumming now exists mainly as a symbol of heritage.

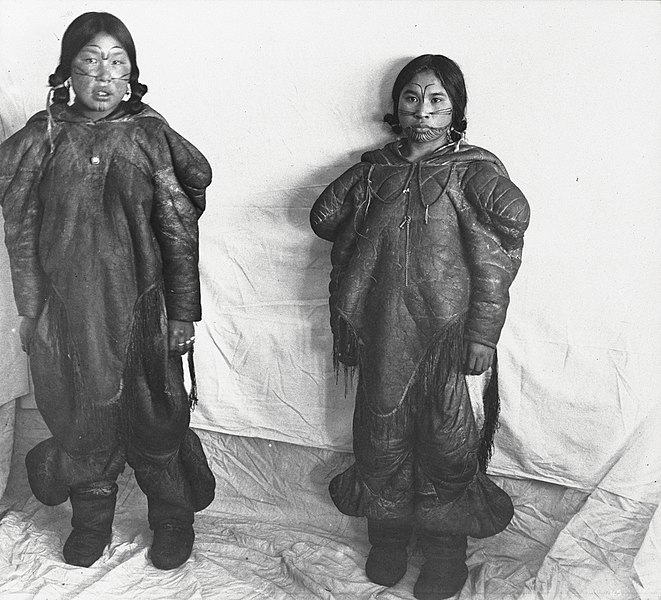

Tattooing – Inuit (Arctic Canada)

Tattooing was a common practice among Inuit women, symbolizing protection, identity, and spiritual connection. These tattoos were created using a traditional stick-and-poke method and adorned the face and hands. The symbols often reflected the environment, like animals or elements of nature, offering the wearer guidance and strength. As European settlers discouraged indigenous customs, the art of Inuit tattooing slowly vanished. Today, many Inuit women are reclaiming the tradition, though it had been largely forgotten for generations. The revival of this cultural practice seeks to restore the deep spiritual and personal significance it once held.

Earth Ovens – Polynesians (Pacific Islands)

Polynesians used earth ovens, or “umu,” to cook food for large feasts. The method involved heating stones, placing the food on top, and covering it with leaves to slow-cook underground. This method was more than just a way to prepare meals; it was a social and spiritual act that brought families together. Over time, modern cooking techniques replaced this ancient method, leading to the decline of umu as an everyday practice. Though it is occasionally revived for special occasions, its regular use has been forgotten by younger generations. The communal and cultural significance of this culinary tradition has largely faded.

Night Fishing – Bajau (Southeast Asia)

The Bajau people, known as sea nomads, practiced night fishing, relying on the stars and natural rhythms to guide them. Fishermen used handcrafted spears and small boats, diving deep into the ocean to catch their prey. It was not only a skill passed down through generations but also a way of life that connected them deeply with the sea. However, environmental degradation and modern fishing methods have diminished the practice. Today, few Bajau continue the tradition, with many adopting modern technology for survival. The spiritual connection to the ocean, once integral to the Bajau identity, is fading into obscurity.

Ritual Basket Weaving – Zulu (South Africa)

Basket weaving was once a sacred art among the Zulu people, where each pattern and color carried symbolic meaning. Baskets were used in ceremonies to store sacred items, and their creation was a meditative, spiritual process. Young girls learned the craft from elders, ensuring the skills and traditions were passed down. As modern materials and storage methods became available, traditional weaving declined, becoming more of a commercial craft than a spiritual one. The symbolic meanings behind the patterns are now understood by few, and the sacredness of the practice has been largely forgotten. Once central to Zulu spirituality, it has become a mere relic of the past.

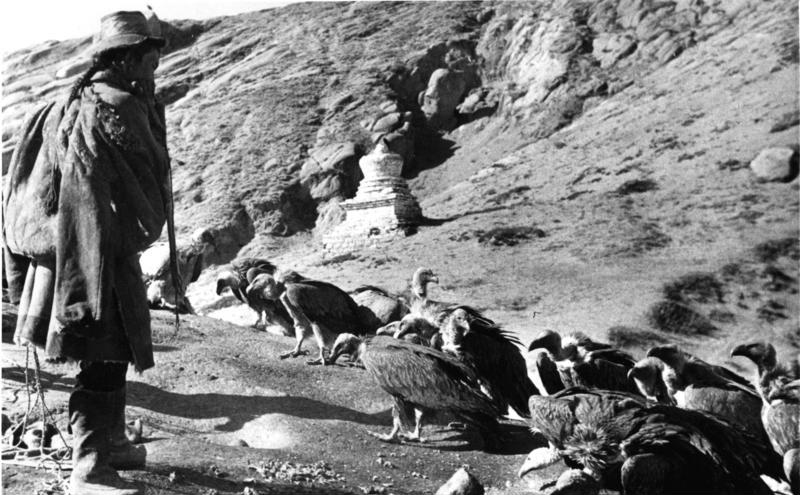

Sky Burial – Tibetan Nomads (Tibet)

Sky burial is an ancient Tibetan practice where the deceased’s body is left in the open air for vultures, symbolizing the return of the body to nature. It was a deeply spiritual act, reflecting the Buddhist belief in the impermanence of the physical body and the continuation of the soul. Families would perform elaborate rituals, praying for the safe passage of the deceased into the afterlife. As Tibet has modernized, fewer families now choose sky burial, opting for more conventional burial methods. The practice is now largely confined to remote areas, and its original spiritual significance has faded. Once a vital part of Tibetan death rituals, sky burials are slowly becoming an obscure tradition.

Gourd Instruments – Ashanti (Ghana)

The Ashanti used hollowed-out gourds as musical instruments, particularly during ceremonial dances and rituals. These gourd instruments, often combined with other natural materials, produced unique, rhythmic sounds central to spiritual and cultural gatherings. They symbolized a connection to the earth and were often handcrafted by community members. With the introduction of modern musical instruments, the use of gourd instruments has sharply declined. Today, they are mainly seen in museums or used as tourist souvenirs. The cultural significance and musical artistry of the gourd, once so deeply integrated into Ashanti life, are slowly being forgotten.

Totem Pole Carving – Haida (North America)

The Haida people of the Pacific Northwest created towering totem poles, intricately carved to tell the stories of their ancestors and clans. Each figure on the pole represented an important cultural symbol, such as an animal or legendary figure, and the process of carving was a sacred act. These poles stood at the entrance of villages, serving as both art and spiritual symbols. Due to colonization and a shift towards more modern practices, totem carving became a rare skill. Although it has seen a resurgence in some Haida communities, the cultural depth and spiritual meaning behind it are not as widespread as they once were. Totem poles now serve more as historical artifacts than the living cultural symbols they once were.

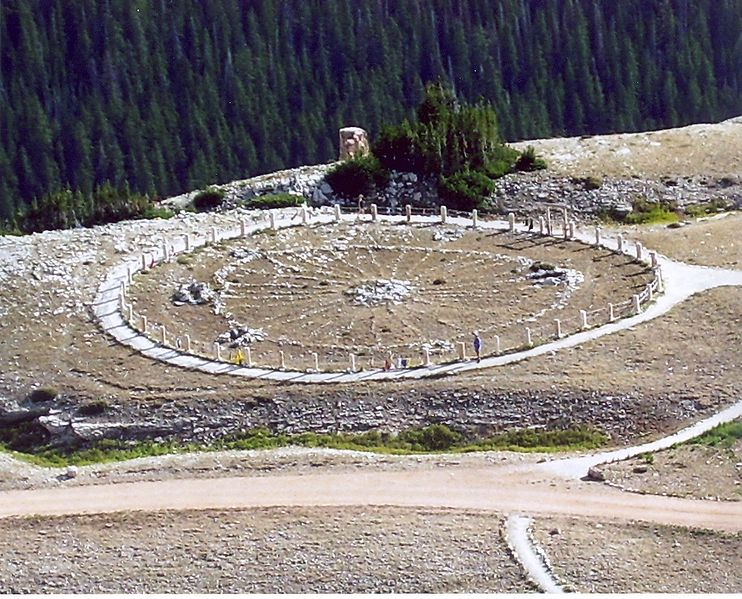

Medicine Wheel Ceremonies – Lakota (Great Plains, USA)

For the Lakota, the medicine wheel was a sacred symbol representing the interconnectedness of life, nature, and the spirit world. Ceremonies performed around the wheel were deeply spiritual, involving prayer, dance, and offerings to the spirits. Each direction of the wheel held a specific meaning, related to the elements, animals, and life stages. As the Lakota were forced into reservations and Christianity spread, the use of the medicine wheel waned. Today, it is more of a cultural symbol than a ritual practice. The spiritual ceremonies, once integral to the Lakota way of life, are rarely performed in their full traditional form.

This article originally appeared on Rarest.org.

More From Rarest.Org

Coral reefs are home to some of the most vibrant and diverse fish species in the world. These underwater ecosystems showcase a kaleidoscope of colors and fascinating behaviors that captivate anyone who visits. Read more.

Throughout the world, certain animals have become powerful symbols of conservation efforts. These creatures often face extreme threats, from habitat loss to poaching. They represent the urgent need to protect biodiversity and maintain a balanced ecosystem. Read more.

Insects are some of the most vital organisms in ecosystems around the world. Though small, they impact everything from pollination to decomposing organic matter. Read more.